The New York Times

September 30, 2004

Global Warming Is Expected to Raise Hurricane Intensity

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

lobal

warming is likely to produce a significant increase in the intensity and

rainfall of hurricanes in coming decades, according to the most comprehensive

computer analysis done so far.

lobal

warming is likely to produce a significant increase in the intensity and

rainfall of hurricanes in coming decades, according to the most comprehensive

computer analysis done so far.

By the 2080's, seas warmed by rising atmospheric concentrations of

heat-trapping greenhouse gases could cause a typical hurricane to intensify

about an extra half step on the five-step scale of destructive power, says the

study, done on supercomputers at the Commerce Department's Geophysical Fluid

Dynamics Laboratory in Princeton, N.J. And rainfall up to 60 miles from the core

would be nearly 20 percent more intense.

Other computer modeling efforts have also predicted that hurricanes will grow

stronger and wetter as a result of global warming. But this study is

particularly significant, independent experts said, because it used half a dozen

computer simulations of global climate, devised by separate groups at

institutions around the world. The long-term trends it identifies are

independent of the normal lulls and surges in hurricane activity that have been

on display in recent decades.

The study was published online on Tuesday by The Journal of Climate and can

be found at www.gfdl.noaa.gov/reference/bibliography/2004/tk0401.pdf.

The new study of hurricanes and warming "is by far and away the most

comprehensive effort" to assess the question using powerful computer

simulations, said Dr. Kerry A. Emanuel, a hurricane expert at the Massachusetts

Institute of Technology who has seen the paper but did not work on it. About the

link between the warming of tropical oceans and storm intensity, he said, "This

clinches the issue."

Dr. Emanuel and the study's authors cautioned that it was too soon to know

whether hurricanes would form more or less frequently in a warmer world. Even as

seas warm, for example, accelerating high-level winds can shred the towering

cloud formations of a tropical storm.

But the authors said that even if the number of storms simply stayed the

same, the increased intensity would substantially increase their potential for

destruction.

Experts also said that rising sea levels caused by global warming would lead

to more flooding from hurricanes - a point underlined at the United Nations this

week by leaders of several small island nations, who pleaded for more attention

to the potential for devastation from tidal surges.

The new study used four climate centers' mathematical approximations of the

physics by which ocean heat fuels tropical storms.

With almost every combination of greenhouse-warmed oceans and atmosphere and

formulas for storm dynamics, the results were the same: more powerful storms and

more rainfall, said Robert Tuleya, one of the paper's two authors. He is a

hurricane expert who recently retired after 31 years at the fluid dynamics

laboratory and teaches at Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va. The other

author was Dr. Thomas R. Knutson of the Princeton laboratory.

Altogether, the researchers spawned around 1,300 virtual hurricanes using a

more powerful version of the same supercomputer simulations that generates

Commerce Department forecasts of the tracks and behavior of real hurricanes.

Dr. James B. Elsner, a hurricane expert at Florida State University who was

among the first to predict the recent surge in Atlantic storm activity, said the

new study was a significant step in examining the impacts of a warmer future.

But like Dr. Emanuel, he also emphasized that the extraordinary complexity of

the oceans and atmosphere made any scientific progress "baby steps toward a

final answer."

New York Times

September 30, 2004

Russian Government Backs U.N. Accord on Global Warming

By REUTERS

Filed at 9:51 a.m. ET

MOSCOW (Reuters) - The Russian government approved the Kyoto Protocol

Thursday, giving decisive support to the long-delayed climate change treaty that

should allow it to come into force worldwide.

The controversial pact will now be passed to the Kremlin-dominated parliament

for ratification.

President Vladimir Putin's government acted despite worries by many officials

who say the 1997 U.N. pact, which orders cuts in greenhouse gas emissions to

slow global warming, would harm the economy and not protect the environment.

The European Union hailed Moscow's decision and seized the moment to urge

Washington, whose rejection of the pact in 2001 left it dependent on Russia's

approval, to rethink its position.

``The fate of the Kyoto protocol depends on Russia. If we... rejected

ratification, we would become the ones to blame (for its failure),'' Deputy

Foreign Minister Yuri Fedotov told the cabinet meeting.

Russia, which accounts for 17 percent of world emissions, has held the key to

Kyoto's success or failure since the United States pulled out.

The pact becomes binding once it has been ratified by 55 percent of the

signatories which must, among them, account for 55 percent of developed

countries' carbon dioxide emissions.

Kyoto has surpassed the first requirement as 122 nations have ratified it.

But without Russia they account for only 44 percent of total emissions.

Russia, a signatory of the pact, initially prevaricated on ratification. But

in May Putin backed it in exchange for EU agreement on the terms of Moscow's

admission to the World Trade Organization.

``We warmly welcome the decision,'' a European Commission spokesman said in

Brussels. He added that the EU now encouraged Washington to review its attitude

to the pact. Environmentalists and experts were equally positive.

``Now he (Putin) can go down in history as the savior (of Kyoto),'' said

Benito Mueller, an expert on the issue for British-based think-tank the Royal

Institute for International Affairs.

BATTLES STILL AHEAD

However, Thursday's meeting left unanswered the question of when parliament

could practically debate ratification. Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov, who was

absent from the cabinet meeting, predicted a tough battle in the State Duma, the

lower house.

``The discussion on the subject is open and debate is likely to be

difficult,'' Fradkov was quoted by Interfax news agency as saying on a visit to

the Netherlands.

Proponents of Kyoto say that apart from contributing to environmental

security worldwide, Russia would be encouraged to upgrade its industries to

match new standards and could earn billions of dollars selling excess quotas for

gas emissions.

But opponents said Russia was likely to be the loser.

``The Academy of Science confirms its position that the protocol is not

effective and gives us no advantages,'' the head of the academy's institute on

climate change and ecology, Yuri Izrael, told the cabinet meeting.

Putin's economic adviser Andrei Illarionov warned that new environmental

standards would cost industry more and undermine the Kremlin's plan to double

gross domestic product in 10 years.

``Many economic calculations show that if the protocol is ratified, the

doubling of GDP becomes impossible in the next 10 years,'' Illarionov said.

``This will require changes in the social and economic policies.''

But the influential head of Duma's international affairs committee,

Konstantin Kosachev, said that, despite differences, parliament had the means to

ratify Kyoto smoothly now that the government had expressed its will.

``There seems to be a consensus over the political importance of Kyoto, while

economic and ecological consequences are the issues causing trouble,'' he told

reporters.

``If the government decided the pact should be ratified, it must have thought

that the latter two are not that important.''

There is no official time limit for the cabinet to send a ratification

request to the Duma. Kosachev said that if it was quick in coming, his committee

could consider it by the end of the year to prepare for a full-session debate.

Interfax said ministries linked to the environment had been given three

months to work out practical measures arising from Russia's obligations.

Government officials have said that Russia needs changes in environmental

legislation, new regulations on measuring emissions and rules for trading

quotas.

October 1, 2004 New York Times

With Russia's Nod, Treaty on Emissions Clears Last Hurdle

By SETH MYDANS and

ANDREW C. REVKIN

OSCOW,

Sept. 30 - The long-delayed Kyoto Protocol on global warming overcame its last

critical hurdle to taking effect around the world on Thursday when Russia's

cabinet endorsed the treaty and sent it to Parliament. The treaty, the first to

require cuts in emissions linked to global warming, would take effect 90 days

after Parliament's approval, a formality that was widely expected.

OSCOW,

Sept. 30 - The long-delayed Kyoto Protocol on global warming overcame its last

critical hurdle to taking effect around the world on Thursday when Russia's

cabinet endorsed the treaty and sent it to Parliament. The treaty, the first to

require cuts in emissions linked to global warming, would take effect 90 days

after Parliament's approval, a formality that was widely expected.

The United States has rejected the treaty and will not be bound by its

restrictions. But the treaty, which has already been ratified by 120 countries

will take effect if supporters include nations accounting for at least 55

percent of all industrialized countries' 1990-level emissions. The only way for

it to cross that threshold was with ratification by Russia. In 1990, the United

States accounted for 36.1 percent of emissions from industrialized countries,

and Russia 17.4 percent.

The protocol was dormant over the last two years as Russia considered its

merits and sought concessions from the European Union, the treaty's main

proponent.

The treaty is widely considered a milestone of international environmental

diplomacy. It is the first agreement that sets binding restrictions on emissions

of heat-trapping gases that, for now, remain an unavoidable result of almost any

facet of modern life, including driving a car and running a power plant. The

main source of the dominant gas, carbon dioxide, is burning coal and oil.

But many specialists say that, at the same time, the protocol is just the

tiniest initial step toward limiting the human influence on the climate, given

that its targets are small and that the United States will not be bound by its

terms. China, a major polluter that did sign the treaty, is not bound by its

restrictions because it is considered a developing country.

The treaty would require 36 industrialized countries to reduce their

collective emissions of six greenhouse gases by 2012 to more than five percent

below 1990 levels, with different targets negotiated for individual countries.

By one calculation, it would take more than 40 times the emissions reductions

required under the treaty to prevent a doubling of the pre-industrial

concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere in this century.

Still, the decision by the government of President Vladimir V. Putin to

endorse the treaty was "cause for celebration," said Klaus Toepfer, the

executive director of the United Nations Environment Program.

He acknowledged that the Kyoto accord was "only the first step in a long

journey towards stabilizing greenhouse gas emissions." But Mr. Toepfer added

that Russia's move sent a vital signal to developing countries, which supported

the treaty only if it excused them from reductions, and the small number of

wealthy nations that still oppose curbs on the gases that cause global warming,

most notably the United States.

"I hope other nations, some of whom, like Russia, have maybe been in the past

reluctant to ratify, will now join us in this truly global endeavor," he said.

In Washington, Harlan L. Watson, the chief State Department negotiator on

climate issues, said Russia's decision would not change the Bush

administration's rejection of the treaty. Mr. Watson said the United States

would continue to focus on long-term research to find new nonpolluting sources

of energy or ways to limit the buildup of carbon dioxide.

A spokesman for

Senator John Kerry, the

Democratic presidential candidate, who has criticized the Bush administration's

position on global warming, was quick to seize on Russia's decision. "George

Bush made a catastrophic mistake when he declared a decade's work of 160 nations

dead on arrival instead of working with our allies to fix the treaty and lead on

global warming,'' said the spokesman, David Wade. "We're still paying a heavy

price for his unilateralism."

One more step is required in Russia for the pact to take effect - approval by

the Parliament, or Duma. But the body is dominated by supporters of Mr. Putin,

so approval is expected, even though Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov predicted a

"difficult debate." The treaty would take effect 90 days after the Duma

approval.

Mr. Putin made no public statement on Thursday. His top economic adviser,

Andrei Illarionov, who had opposed the pact, said that the decision to endorse

it had been made for political reasons and that the task now would be to try to

minimize what he called the treaty's negative consequences for Russia.

He said compliance would slow Russia's economic growth and make it impossible

to meet Mr. Putin's stated goal of doubling the gross domestic product within a

decade.

"It's not a decision we are making with pleasure," Mr. Illarionov said, the

Interfax news agency reported.

The European Union had pressed Russia for more than a year to accept the

pact. In Brussels, Romano Prodi, the president of the European Commission, said

"President Putin has sent a strong signal of his commitment and sense of

responsibility."

Mr. Illarionov had said the treaty was based on false and even deceptive

scientific assumptions.

His views conflict with a broad international scientific consensus that the

buildup of long-lived gases, which act like the panes in a greenhouse roof, is

likely to disrupt weather patterns and water supplies and threaten coasts by

raising sea levels.

German Gref, Russia's economic development minister, called the treaty "a

progressive step" but said, "It will hardly be decisive in radically improving

the environmental situation."

Breaking with Mr. Illarionov, Mr. Gref added that the treaty was unlikely to

undermine Russia's economic growth.

In Washington, some lobbyists for American industries opposed to the treaty

suggested there was a chance that Mr. Putin still opposed it and was planning

for Parliament to reject it - as proof that he was not consolidating power.

But in Moscow, the mood among environmental activists was cautiously upbeat.

Vladimir Azkharov, director of the Center for Russian Environmental Policy, a

lobbying group, said the treaty "very, very probably" would be approved in

parliament, although he said, "there is no guarantee."

President Bush summarily rejected the treaty in 2001, saying it would burden

the economy by limiting use of fossil fuels and would unfairly exclude big

developing countries from curbs on emissions. The Senate had long ago signaled

its opposition for the same reasons.

China and other developing countries, while signing the treaty, only did so

because it obligated established industrial powers to act first.

Last December, in what seemed a definitive rejection, Mr. Illarionov said

Russia would not sign the treaty. In May, however, Mr. Putin promised to speed

ratification, in a move widely interpreted as a concession to gain support from

the European Union for Russia's bid to join the World Trade Organization.

International environmental groups expressed satisfaction at the news.

"As the Earth is battered by increasing storms, floods and droughts,

President Putin has brought us to a pivotal point in human history," Steve

Sawyer, a climate campaigner for Greenpeace International, said. "The Bush

administration is out in the cold and the rest of the world can move forward."

In a telephone interview, Fred Krupp, the president of Environmental Defense,

said, "What is significant is that it will be a market signal heard around the

world, a signal that we are moving into a carbon-constrained future."

The treaty, named for the Japanese city of Kyoto where it was negotiated in

1997, is an outgrowth of a 1992 pact, the United Nations Framework Convention on

Climate Change, that was signed by Mr. Bush's father and under which countries

agreed to strive to bring their emissions of the gases to 1990 levels by 2000.

By the mid-1990s, however, it was clear that the targets would not be met,

leading to a new round of talks toward a binding protocol with firm targets and

penalties.

Its basic architecture and targets were hastily negotiated in December 1997

in Kyoto. But momentum was lost after Mr. Bush rejected it and after the attacks

of Sept. 11, 2001.

Some of its biggest weaknesses now stem from the long delays. Subsequent

economic activity and rising emissions have threatened to put Europe and Japan,

its main backers, out of compliance.

The treaty provides various strategies through which countries can reach

their targets without actually reducing emissions at home. Investments can be

made in poor countries to save forests, which absorb carbon dioxide, or

introduce efficient technologies, which use less fuel.

It permits emissions trading, in which one country buys the right to emit

from another that has already exceeded its targets for reducing emissions and

has extra credits.

Prof. David G. Victor, a political scientist at Stanford and longtime student

of the protocol, said Russia had nothing to lose by moving ahead, since it

surpassed its Kyoto targets before they were set.

After the Russian economy collapsed with the fall of Communism, the country's

greenhouse gas emissions fell far below 1990 levels, leaving it with a bonanza

of tradable credits earned when it surpassed its targets for reducing emissions.

For Europe this bundle of credits is a mixed blessing now, Mr. Victor said.

The European Union recently passed legislation creating an internal trading

market under the protocol's terms, so that richer member states, like Britain,

could get credit toward targets by investing in emissions-cutting projects in

poorer, more polluted, ones, like Spain. But under the treaty's terms, Europe,

Japan, and other industrialized participants can buy credits from Russia as

well. If Russia now starts selling its credits to Europe, there will be little

incentive for companies within the European Union to push ahead with plans to

cut emissions that would be more costly, Mr. Victor said.

Seth Mydans reported from Moscow for this article, and Andrew C.Revkin

from Washington.

|

Source:

|

|

|

|

Date:

|

2004-10-08

|

|

|

Drought In The West Linked To Warmer Temperatures

Severe drought in western states in recent years may be linked

to climate warming trends, according to new research led by scientists from the

Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory of Columbia University to be posted October 7

on Science magazine's website,

http://www.sciencemag.org. This research was supported by the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the National Science

Foundation (NSF).

Analyzing aridity in the western U.S. over the past 1,200 years, the study

team, which also included scientists from the University of Arizona, University

of Arkansas, and NOAA, found evidence suggesting that elevated aridity in the

U.S. West may be a natural response to climate warming. "The Western United

States is so vulnerable to drought, we thought it was important to understand

some of the long-term causes of drought in North America," said lead author Dr.

Edward R. Cook of the Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory's tree ring laboratory.

The study revealed that a 400-year-long period of elevated aridity and epic

drought occurred in what is now the western U.S. during the period A.D.

900-1300. This corresponds broadly to the so-called "Medieval Warm Period," a

time in which a variety of paleoclimate records indicate unusual warmth over

much of the Northern Hemisphere. The authors of the new study argue that there

are climate mechanisms involved that make warming climate conditions likely to

lead to increased prevalence of drought in the western, interior region of North

America.

Looking at implications for the future, the authors express concern. "Any

trend towards warmer temperatures in the future could lead to a serious

long-term increase in aridity over Western North America," they write in the

paper.

Co-author Dr. David Meko of the University of Arizona tree ring lab notes

that the drought that has gripped the western United States for the past four

years "pales in comparison with some of the earlier droughts we see from the

tree-ring record. What would really put a stress on society is decade-long

drought."

"If warming over the tropical Pacific Ocean promotes drought over the western

U.S., this is a potential problem for the future in a world that is increasingly

subjected to greenhouse warming," Dr. Cook added.

The study's authors used tree ring records to reconstruct evidence of

drought, and also looked at a number of independent drought indicators ranging

from elevated charcoal in lake sediments to sand dune activation records. The

team then used published climate model studies to explore mechanisms that link

warming with aridity in the western U.S.

In addition to the paper in Science, they also used the data to create a

CD-ROM called the North American Drought Atlas, the first of its kind, providing

a history of drought on this continent. The atlas contains annual maps of

reconstructed droughts over North America, an animation of those maps showing

aridity over time, and a time series plot of each reconstruction with associated

plots of calibrated and verification statistics. The North American Drought

Atlas CD-ROM can be obtained by contacting Dr. Edward R. Cook at Lamont-Doherty

Earth Observatory

(drdendro@ldeo.columbia.edu).

### The Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory is part of the Earth Institute at

Columbia University, the world's leading academic center for the integrated

study of Earth, its environment, and society. The Earth Institute builds upon

excellence in the core disciplines–earth sciences, biological sciences,

engineering sciences, social sciences and health sciences–and stresses

cross-disciplinary approaches to complex problems. Through its research training

and global partnerships, it mobilizes science and technology to advance

sustainable development, while placing special emphasis on the needs of the

world's poor. For more information please visit

http://www.earth.columbia.edu.

This story has been adapted from a news release issued by The Earth

Institute At Columbia University.

October 29, 2004

New York Times

Warming Trend in Arctic Is Linked to Emissions

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

he

first thorough assessment of a decadeslong Arctic warming trend shows the region

is undergoing profound changes, including sharp retreats of glaciers and sea

ice, thawing of permafrost, and shifts in ocean and atmospheric conditions that

are likely to harm native communities, wildlife, and economic activities while

offering some benefits, as well.

he

first thorough assessment of a decadeslong Arctic warming trend shows the region

is undergoing profound changes, including sharp retreats of glaciers and sea

ice, thawing of permafrost, and shifts in ocean and atmospheric conditions that

are likely to harm native communities, wildlife, and economic activities while

offering some benefits, as well.

The report, while noting that conditions in the far north have varied

naturally in the past, says the current shifts match longstanding scientific

projections that the Arctic should be the first place to feel the impact of

rising atmospheric concentrations of heat-trapping greenhouse gases from

smokestacks and tailpipes.

It adds that the warming and other changes are likely to accelerate in this

century because of the ongoing buildup in greenhouse gases.

Prompt efforts to curb such emissions could slow the pace of change

sufficiently to allow communities and wildlife to adapt, the report says. But it

also stresses that some further warming and melting is unavoidable given the

centurylong buildup of the long-lived gases, mainly carbon dioxide.

"These changes in the Arctic provide an early indication of the environmental

and societal significance of global warming," the executive summary of the

report says.

The study, called the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, was commissioned four

years ago by the eight nations with Arctic territory - Canada, Denmark, Finland,

Iceland, Norway, the Russian Federation, Sweden and the United States - and

conducted and reviewed by 250 scientists and representatives of six

organizations representing Arctic native communities.

The study was scheduled for release at a conference in Iceland on Nov. 9, but

electronic copies of some portions were provided to The New York Times by

European participants in the project, several of whom said that publication had

been delayed in part by the Bush administration because of the political

contentiousness of global warming.

Officials of the Arctic Council, the international body that commissioned the

study, denied that was the case. "There is no truth to the contention that any

of the member states of the

Arctic Council pushed the release of the report back into November," said

Gunnar Palsson of Iceland, the chairman of the council's eight government

representatives. A State Department official declined to comment directly on the

Arctic report, saying that Mr. Palsson spoke for the council.

He said that the countries all agreed to delay the issuance to November from

September because of conflicts with another international meeting in Iceland.

The American scientist directing the assessment, Dr. Robert W. Corell, an

oceanographer and senior fellow of the American Meteorological Society, said the

timing was set during diplomatic discussions that did not involve the

scientists.He said he could not yet comment on the specific findings, but noted

that the signals from the Arctic have global significance.

"The major message is that climate change is here and now in the Arctic," he

said today. "The scientific evidence of the last 25 to 30 years is very dramatic

and substantial. The projections of future change indicate that this trend will

continue and be substantially greater than the trends we're seeing on a global

scale."

The report is a profusely illustrated window on a region in remarkable flux,

incorporating reams of scientific data as well as observations by elders from

communities around the Arctic Circle.

The potential benefits of the changes include projected growth in marine fish

stocks and improved prospects for agriculture and timber harvests in some

regions, as well as expanded access to Arctic waters.

There, sea-bed deposits of oil and gas that have until now been cloaked in

thick shifting crusts of sea ice could soon be exploitable, and ice-free trade

routes over Siberia could significantly cut shipping distances between Europe

and Asia in the summer. But the list of potential harms is far longer.

The same retreat of sea ice, it says, "is very likely to have devastating

consequences for polar bears, ice-living seals and local people for whom these

animals are a primary food source."

Oil and gas deposits on land are likely to be harder to extract as tundra

continues to thaw, limiting the frozen season when drilling convoys can traverse

the otherwise spongy ground, the report says. Alaska has already seen the

"tundra travel" season on the North Slope shrink from about 200 days a year in

1970 to 100 days now.

And it concludes that the consequences of the fast-paced Arctic warming have

global reach, in part as sea levels rise in response to the accelerated melting

of Greenland's two-mile-high sheets of ice.

There have been continuing disagreements between American officials and other

participants over the report's contents and timetable.

Last year, for example, the State Department distributed a document to

representatives from the other Arctic countries saying that it opposed having

the technical experts draw conclusions about policies on greenhouse gases or

other related factors until the scientific findings had been reviewed by the

eight participating governments.

A copy was provided to The New York Times by a person involved in the project

who criticized the delay in considering the implications of the climate shifts.

The document said this was "a fundamental flaw" in the process. The

implications of the findings could not be legitimately considered before the

scientific assessment was completed and governments needed to have the right to

suggest changes.

Big Arctic Perils Seen in Warming, Survey Finds

By ANDREW C. REVKIN

comprehensive four-year study of warming in the Arctic shows that heat-trapping

gases from tailpipes and smokestacks around the world are contributing to

profound environmental changes, including sharp retreats of glaciers and sea

ice, thawing of permafrost and shifts in the weather, the oceans and the

atmosphere.

comprehensive four-year study of warming in the Arctic shows that heat-trapping

gases from tailpipes and smokestacks around the world are contributing to

profound environmental changes, including sharp retreats of glaciers and sea

ice, thawing of permafrost and shifts in the weather, the oceans and the

atmosphere.

The study, commissioned by eight nations with Arctic territory, including the

United States, says the changes are likely to harm native communities, wildlife

and economic activity but also to offer some benefits, like longer growing

seasons. The report is due to be released on Nov. 9, but portions were provided

yesterday to The New York Times by European participants in the project.

While Arctic warming has been going on for decades and has been studied

before, this is the first thorough assessment of the causes and consequences of

the trend.

It was conducted by nearly 300 scientists, as well as elders from the native

communities in the region, after representatives of the eight nations met in

October 2000 in Barrow, Alaska, amid a growing sense of urgency about the

effects of global warming on the Arctic.

The findings support the broad but politically controversial scientific

consensus that global warming is caused mainly by rising atmospheric

concentrations of heat-trapping greenhouse gases, and that the Arctic is the

first region to feel its effects. While the report is advisory and carries no

legal weight, it is likely to increase pressure on the Bush administration,

which has acknowledged a possible human role in global warming but says the

science is still too murky to justify mandatory reductions in greenhouse-gas

emissions.

The State Department, which has reviewed the report, declined to comment on

it yesterday.

The report says that "while some historical changes in climate have resulted

from natural causes and variations, the strength of the trends and the patterns

of change that have emerged in recent decades indicate that human influences,

resulting primarily from increased emissions of carbon dioxide and other

greenhouse gases, have now become the dominant factor."

The Arctic "is now experiencing some of the most rapid and severe climate

change on Earth," the report says, adding, "Over the next 100 years, climate

change is expected to accelerate, contributing to major physical, ecological,

social and economic changes, many of which have already begun."

Scientists have long expected the Arctic to warm more rapidly than other

regions, partly because as snow and ice melt, the loss of bright reflective

surfaces causes the exposed land and water to absorb more of the sun's energy.

Also, warming tends to build more rapidly at the surface in the Arctic because

colder air from the upper atmosphere does not mix with the surface air as

readily as at lower latitudes, scientists say.

The report says the effects of warming may be heightened by other factors,

including overfishing, rising populations, rising levels of ultraviolet

radiation from the depleted ozone layer (a condition at both poles). "The sum of

these factors threatens to overwhelm the adaptive capacity of some Arctic

populations and ecosystems," it says.

Prompt efforts to curb greenhouse-gas emissions could slow the pace of

change, allowing communities and wildlife to adapt, the report says. But it also

stresses that further warming and melting are unavoidable, given the

century-long buildup of the gases, mainly carbon dioxide.

Several of the Europeans who provided parts of the report said they had done

so because the Bush administration had delayed publication until after the

presidential election, partly because of the political contentiousness of global

warming.

But Gunnar Palsson of Iceland, chairman of the Arctic Council, the

international body that commissioned the study, said yesterday that there was

"no truth to the contention that any of the member states of the Arctic Council

pushed the release of the report back into November." Besides the United States,

the members are Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia and Sweden.

Mr. Palsson said all the countries had agreed to delay the release,

originally scheduled for September, because of conflicts with another

international meeting in Iceland.

The American scientist directing the assessment, Dr. Robert W. Corell, an

oceanographer and senior fellow of the American Meteorological Society, said the

timing was set during diplomatic discussions that did not involve the

scientists.

He said he could not yet comment on the specific findings, but noted that the

signals from the Arctic have global significance.

"The major message is that climate change is here and now in the Arctic," he

said.

The report is a profusely illustrated window on a region in remarkable flux,

incorporating reams of scientific data as well as observations by elders from

native communities around the Arctic Circle.

The potential benefits of the changes include projected growth in marine fish

stocks and improved prospects for agriculture and timber harvests in some

regions, as well as expanded access to Arctic waters.

But the list of potential harms is far longer.

The retreat of sea ice, the report says, "is very likely to have devastating

consequences for polar bears, ice-living seals and local people for whom these

animals are a primary food source."

Oil and gas deposits on land are likely to be harder to extract as tundra

thaws, limiting the frozen season when drilling convoys can traverse the

otherwise spongy ground, the report says. Alaska has already seen the "tundra

travel" season on the North Slope shrink to 100 days from about 200 days a year

in 1970.

The report concludes that the consequences of the fast-paced Arctic warming

will be global. In particular, the accelerated melting of Greenland's

two-mile-high sheets of ice will cause sea levels to rise around the world.

Arctic thaw big threat, study says

FROM WIRE REPORTS Arizona Daily Star 11-9-04

WASHINGTON - Global warming is heating the Arctic almost twice as fast as

the rest of the planet in a thaw that threatens millions of livelihoods and

could wipe out polar bears by 2100, an eight-nation report said on Monday.

The biggest survey to date of the Arctic climate, by 250 scientists, said

the accelerating melt could be a foretaste of wider disruptions from a buildup

of human emissions of heat-trapping gases in the Earth's atmosphere.

The "Arctic climate is now warming rapidly and much larger changes are

projected," according to the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, funded by the

United States, Canada, Russia, Denmark, Iceland, Sweden, Norway and Finland.

The study said the annual average amount of sea ice in the Arctic has

decreased about 8 percent in the past 30 years, resulting in the loss of

386,100 square miles of sea ice - an area bigger than Texas and Arizona

combined.

"The polar regions are essentially the Earth's air conditioner," Michael

MacCracken, president of the International Association of Meteorology and

Atmospheric Sciences, said at a news conference Monday. "Imagine the Earth

having a less efficient air conditioner."

Pointing to the report as a clear signal that global warming is real, Sens.

John McCain, R-Ariz., and Joe Lieberman, D-Conn., said the "dire consequences"

of warming in the Arctic underscore the need for their proposal to require

U.S. cuts in emissions of carbon dioxide and other heat-trapping greenhouse

gases.

President Bush has rejected that approach.

James Connaughton, chairman of the White House Council on Environmental

Quality, said the Bush administration is spending $10 billion yearly on

research into climate change and related issues.

"The president's strategy on climate change is quite detailed," he said.

Farming could benefit in some areas, while more productive forests are

moving north onto former tundra.

"There are not just negative consequences, there will be new opportunities,

too," said Paal Prestrud, vice-chair of the Arctic Climate Impact Assessment.

Possible benefits like more productive fisheries, easier access to oil and

gas deposits or trans-Arctic shipping routes would be outweighed by threats to

indigenous peoples and the habitats of animals and plants.

Sea ice around the North Pole, for instance, could almost disappear in

summer by the end of the century.

"Polar bears are unlikely to survive as a species if there is an almost

complete loss of summer sea-ice cover," the report said. On land, creatures

like lemmings, caribou, reindeer and snowy owls are being squeezed north into

a narrower range.

The report mainly blames the melt on gases from fossil fuels burned in

cars, factories and power plants. The Arctic warms faster than the global

average because dark ground and water, once exposed, traps more heat than

reflective snow and ice.

Many of the 4 million people in the Arctic are already suffering. Buildings

from Russia to Canada have collapsed because of subsidence linked to thawing

permafrost that also destabilizes oil pipelines, roads and airports.

Indigenous hunters are falling through thinning ice and say that prey from

seals to whales is harder to find. Rising levels of ultraviolet radiation may

cause cancers.

The White House said it would not comment on Monday's findings but would

await the full report next year.

"This is one draft of a report that has yet to be finished," White House

spokesman Trent Duffy said.

In the past 50 years, average yearly temperatures in Alaska and Siberia

rose by about 3.6 degrees to 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit, and winters in Alaska and

western Canada warmed an average of 5 degrees to 7 degrees Fahrenheit.

With "some of the most rapid and severe climate change on Earth," the

Arctic regions' melting contributed to sea levels rising globally by an

average of about 3 inches in the past 20 years, the report said.

Sea levels globally already are expected to rise between another 4 inches

to 3 feet or more this century.

"These changes in the Arctic provide an early indication of the

environmental and societal significance of global warming," the study says.

The study projects that in the next 100 years, the yearly average

temperatures will increase by 7 to 13 degrees Fahrenheit over land and 13 to

18 degrees over the ocean, mainly because the water absorbs more heat.

Forests would expand into Arctic tundra, which in turn would expand into

polar ice deserts since rising temperatures favor taller, denser vegetation.

Arctic tundra would shrink to its smallest extent since 21,000 years ago when

humans began emerging from an Ice Age.

Climate Uncertainty With CO2 Rise Due To Uncertainty About Aerosols

UPTON, NY - Climate scientists agree that atmospheric carbon

dioxide (CO2) has increased about 35 percent over the industrial period and that

it will continue to rise so that CO2 will reach double its pre-industrial value

well before the end of this century. How much this doubled CO2 concentration

will raise Earth’s global mean temperature, however, remains quite uncertain and

is the subject of intense research — and heated debate.

|

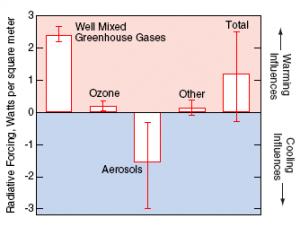

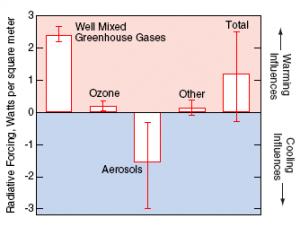

This graph shows estimates of the influences of various factors

(greenhouse gases, ozone, aerosols, and other) on climate change over the

industrial period, and their combined total influence. Red brackets

indicate the range of uncertainty for each factor and the total. The

uncertainty for the "total" estimate is so large because of the large

uncertainty in the estimated influence of aerosols. Shrinking the

uncertainty associated with the total to a value that is useful for

interpreting Earths climate sensitivity requires a major reduction in the

uncertainty associated with the influence of aerosols. (Graphic courtesy

of Brookhaven National Laboratory)

|

In a paper to be published in the November issue of the Journal of the Air

and Waste Management Association, Stephen Schwartz, an atmospheric scientist at

the U.S. Department of Energy’s Brookhaven National Laboratory, argues that much

of the reason for the present uncertainty in the climatic effect of increased

CO2 arises from uncertainty about the influence of atmospheric aerosols, tiny

particles in the air. Schwartz, who is also chief scientist of the Department of

Energy’s Atmospheric Science Program, points out that aerosols scatter and

absorb light and modify the properties of clouds, making them brighter and thus

able to reflect more incoming solar radiation before it reaches Earth’s surface.

“Because these aerosol particles, like CO2, are introduced into the

atmosphere as a consequence of industrial processes such as fossil fuel

combustion,” says Schwartz, “they have been exerting an influence on climate

over the same period of time as the increase in CO2, and could thus very well be

masking much of the influence of that greenhouse gas.” However, he emphasizes,

the influence of aerosols is not nearly so well understood as the influence of

greenhouse gases.

As Schwartz documents, the uncertainty in the climate influence of

atmospheric aerosols limits any inference that can be drawn about future climate

sensitivity — how much the temperature would rise due to CO2 doubling alone —

from the increase in global mean temperature already observed over the

industrial period.

The global warming of 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 degrees Fahrenheit) that has

taken place since 1900 suggests that, if there were no aerosol influence, the

effect of CO2 doubling on mean global temperature would be rather low — a rise

of 0.9 degrees Celsius (1.6 degrees Fahrenheit). But, the likelihood that

aerosols have been offsetting some of the warming caused by CO2 all along, says

Schwartz, means that the observed 0.5-degree-Celsius temperature rise is just

the part of the CO2 effect we can “see” — the tip of the greenhouse “iceberg.”

So the effect of doubling CO2, holding everything else constant, he says, might

be three or more times as great.

“Knowledge of Earth’s climate sensitivity is central to informed

decision-making regarding future carbon dioxide emissions and developing

strategies to cope with a greenhouse-warmed world,” Schwartz says. However, as

he points out, not knowing how much aerosols offset greenhouse warming makes it

impossible to refine estimates of climate sensitivity. Right now, climate models

with low sensitivity to CO2 and those with high sensitivity are able to

reproduce the temperature change observed over the industrial period equally

well by using different values of the aerosol influence, all of which lie within

the uncertainty of present estimates.

“In order to appreciably reduce uncertainty in Earth’s climate sensitivity

the uncertainty in aerosol influences on climate must be reduced at least

threefold,” Schwartz concludes. He acknowledges that such a reduction in

uncertainty presents an enormous challenge to the aerosol research community.

An editorial accompanying the paper credits Schwartz with presenting “a

unique argument challenging the research community to reduce the uncertainty in

aerosol forcing of climate change in order to reduce the uncertainty in climate

sensitivity to an extent that would be more useful to decision makers.” The

editorial also suggests that, “Schwartz’s calculations are not only of interest

for the issue of climate change but may serve as a paradigm for environmental

issues in general.”

This research was funded by the Office of Biological and Environmental

Research within the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Science.

Editor's Note: The original news release can be found

here.

Published: 11.13.2004

Tom Teepen: Pity the poor polar bear: U.S. still on fence about global

warming warning

Tom Teepen

Really, when you think about it, who needs polar bears? Oh, they are OK to

look at in a zoo, although they don't do tricks like the monkeys, and they are

pleasant enough as extras in Christmastime kiddie movies.

But they make no political contributions and have no lobbyists in

Washington, so, well, easy come, easy go.

The bears' likely extinction by the end of this century is predicted in the

recent report of a four-year study by 300 scientists from the eight nations,

including the United States, that sponsored the Arctic Climate Impact

Assessment.

Going with the polar bears will be some species of seals, several migratory

bird species and assorted other creatures.

In a preview of some of the consequences from unchecked global warming, the

study found that the Arctic regions of the United States, Canada and Russia

have been warming at a rate about 10 times that of the rest of Earth.

Average temperatures have risen 4 to 7 degrees in just the last 50 years.

Arctic ice is melting. It will be turning up as higher sea levels and will

flood, among other places, parts of Florida and Louisiana particularly.

The culprits are the greenhouse gases created by burning fossil fuels. The

scientific consensus on this point is international and nearly universal

except for a few holdouts still on the payrolls of implicated energy and

related industries.

But to hear the U.S. government tell it - at least, the current

administration and depending on which agency is speaking - either global

warming is a fiction gotten up by anti-business socialists or, if it is real,

it is a natural, cyclical phenomenon and the right and proper answer to it is

to quit whining and look on the bright side of how great it is going to be for

water sports.

One of George W. Bush's early acts as president was to take the United

States out of the Kyoto Treaty, which the previous administration had helped

to negotiate.

The treaty's requirements for restraining greenhouse gas emissions would be

bad for business, Bush said, declining even to seek mitigating adjustments.

With Russia's recent ratification of Kyoto, the treaty now has enough

signatories to activate it, and although our State Department keeps saying

Washington will work with the Kyoto nations for the common environmental good,

in fact we have done nothing serious along those lines.

U.S. policy, as a result, is a standing affront to science, to

international concern and cooperation and to common sense.

The rest of the world is left pretty much on its own to solve a problem to

which we are the single largest contributor. (And, yes, some of the signers

will cheat and others default, but the drift will be toward compliance, and

the renegers could be more effectively chastened if we were involved.)

Maybe counting on the lovable polar bears to prevail as the issue's poster

children where science is disdained, the head of the National Environmental

Trust said of this sober Arctic report:

"This is the smoking gun. Skeptics, polluting industries and President Bush

can't run away from this one."

Wanna bet?

● Tom Teepen is a columnist for Cox Newspapers, 72 Marietta St. NW,

Atlanta, GA 30302; e-mail: teepencolumn@coxnews.com.

All content copyright © 1999-2004 AzStarNet,

Arizona Daily Star and its wire services and suppliers and may not be

republished without permission. All rights reserved. Any copying,

redistribution, or retransmission of any of the contents of this service without

the expressed written consent of Arizona Daily Star or AzStarNet is prohibited.

New York Times

December 19, 2004

U.S. Waters Down Global Commitment to Curb Greenhouse Gases

By LARRY ROHTER

BUENOS AIRES, Dec.

18 - Two weeks of negotiations at a United Nations conference here on climate

change ended early Saturday with a weak pledge to start limited, informal talks

on ways to slow down global warming, after the

United States blocked efforts

to begin more substantive discussions.

The main focus was to discuss the Kyoto Protocol on global warming, which

goes into force on Feb. 16 and will require industrial nations to make

substantial cuts in their emissions of so-called greenhouse gases. But another

goal had been to draw the United States, which withdrew from the accord in 2001,

back into discussions about ways to mitigate climate change after 2012, when the

Kyoto agreement expires.

Governments that are already committed to reducing emissions under the Kyoto

plan used diplomatic language to express their disappointment at the American

position. Environmental groups, however, were more critical of what they

characterized as obstructionism.

"This is a new low for the United States, not just to pull out, but to block

other countries from moving ahead on their own path," said Jeff Fiedler, an

observer representing the Washington-based Natural Resources Defense Council.

"It's almost spiteful to say, 'You can't move ahead without us.' If you're not

going to lead, then get out of the way."

Because the United States rejects the Kyoto accord, it cannot take part

except as an observer in talks on global warming held under that format. It has,

however, signed a broader 1992 convention on climate change that is based on

purely voluntary measures, and the European Union and others had hoped to

organize seminars within that framework.

But the United States maintains it is too early to take even that step, and

initially insisted that "there shall be no written or oral report" from any

seminars. In the end, all that could be achieved was an agreement to hold a

single workshop next year to "exchange information" on climate change.

"We are very flexible, but not at all costs," said Pieter van Geel, state

secretary of the environment for the

Netherlands and president of the

European Union delegation. "It must be a meaningful seminar" with "a report

somewhere," he added. "These are very modest things when you start a

discussion."

Delegations and observer groups also criticized what they described as an

effort led by Saudi Arabia and supported by the United States to hamper approval

of so-called adaptation assistance. That term refers to payments that richer

countries would make, mostly to poor, low-lying island countries to help them

cope with the impacts of climate change.

The group that would receive the aid includes Pacific Ocean states like

Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands and Micronesia, and Caribbean nations

like the

Bahamas and Barbados. At a

news conference here on Thursday, their representatives said rising sea levels,

accelerated land erosion and more intense storms were already affecting their

economic development.

But the issue was complicated by Saudi Arabia's insistence that the aid

include compensation to oil-producing countries for any fall in revenues that

may result from the reduction in the use of carbon fuels. The European Union,

which had announced its intention to provide $400 million a year to an

assistance fund, strongly opposed any such provision.

Harlan Watson, a senior member of the American delegation, would not

specifically discuss the American position other than to say there are "always

tos and fros in any negotiation." He described the results as "the most

comprehensive adaptation package that has ever been completed," and "something

that satisfied all parties."

The United States also stood virtually alone in challenging the scientific

assumptions underlying the Kyoto Protocol. "Science tells us that we cannot say

with any certainty what constitutes a dangerous level of warming, and therefore

what level must be avoided," Paula Dobriansky, under secretary of state for

global affairs and the leader of the American delegation, said in her remarks to

the conference.

At a side meeting organized by insurance companies, however, concerns were

expressed about rapidly rising payments resulting from more severe and frequent

hurricanes, heat waves and flooding. Representatives of major European

reinsurance companies described 2004 as "the costliest year for the insurance

industry worldwide" and warned that worse is likely to come.

Thomas Loster, a climate expert at the Munich Re insurance group, estimated

that the cost of disasters will rise to as much as $95 billion annually,

compared to an average of $70 billion over the past decade. Experts here

acknowledge that extreme weather patterns have always existed, but maintain that

their frequency and intensity has been increasing because of global warming.

"There is more and more evidence building up that indicates that whatever is

going on is not natural and is no longer within the realm of variability," said

Alden Meyer, policy director of the Union of Concerned Scientists. Enough

research has been done, especially in the Arctic, he added, to establish that

"we are starting to see the impact of human interference" and "a clear pattern

of human-induced climate change."

Those sharply different perceptions led to a clash even over what language

should be used in discussing disaster relief. Bush administration emissaries

opposed the use of the phrase "climate change," employed since the days of the

first Bush administration, in favor of "climate variability," a much more

nebulous term.

![]() lobal

warming is likely to produce a significant increase in the intensity and

rainfall of hurricanes in coming decades, according to the most comprehensive

computer analysis done so far.

lobal

warming is likely to produce a significant increase in the intensity and

rainfall of hurricanes in coming decades, according to the most comprehensive

computer analysis done so far.