UNTA

ARENAS, Chile — Everything is different here at the bottom of the world,

starting with the weather. Before Alejandra Mundaca lets her two children go

out, she checks the forecast for the temperature, chances of rain and also the

level of ultraviolet rays.

UNTA

ARENAS, Chile — Everything is different here at the bottom of the world,

starting with the weather. Before Alejandra Mundaca lets her two children go

out, she checks the forecast for the temperature, chances of rain and also the

level of ultraviolet rays.

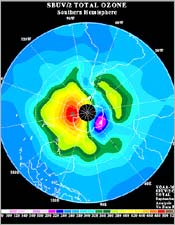

For the last decade the hole in the ozone layer over Antarctica has been

forming earlier in the Southern Hemisphere spring and growing larger. The

125,000 residents of the southernmost city on the planet, here on the Strait of

Magellan, have reluctantly learned to adapt.

They closely watch the color-coded warnings of a "solar stoplight"

publicized on television and radio and even posted on street corners here. Even

on warm days, most people insist on wearing jackets or long-sleeved shirts or

blouses. Many wear sunglasses and make sure to apply 50-proof sunblock even when

the sky is blanketed in clouds.

|

A

"solar stoplight" in Punta Arenas announces an orange alert,

the second highest of four levels, and warns people to limit their

exposure to the sun between noon and 3 p.m. to a maximum of 21 minutes.

|

"Life has changed a lot for us over the past few years, and I know that

my sons are not going to be able to enjoy the same kind of childhood that I had

growing up here," said Ms. Mundaca, 33, a schoolteacher. "We used to

look forward to spring as relief from the long harsh winter, but now it is a

time of maximum peril for all of us who live here."

The ozone layer is a thin covering of gas in the stratosphere that absorbs

most of the sun's ultraviolet rays. Since scientists first discovered the hole

over Antarctica in the mid-1980's, it has nearly doubled in size and now covers

an area larger than North America during the Southern Hemisphere spring. The

arms of the hole occasionally extend as far as southern Chile and Argentina,

depending on wind patterns.

On a typical day here this month, the solar stoplight was set at orange, the

second highest of four levels, and people were warned to limit their exposure to

the sun between noon and 3 p.m. to 21 minutes at most.

"When the light is red, I don't let my kids go out to play at all,"

Liliana Navarro Torres said, referring to Kimberley, 6, and Jonathan, 4.

"They don't like it much, and sometimes it drives me crazy to have them

running around the house, but that's the way it has to be when you live

here."

|

In

Punta Arenas, Chile, where residents have learned to adapt to the hole

in the ozone layer, a woman and her child are bundled up against the sun

beside a monument honoring Ferdinand Magellan.

|

|

In

the city's schools, the children are taught how to protect themselves

against ultraviolet rays.

|

The growth of the ozone hole is attributed largely to chlorofluorocarbons, or

CFC's, that were widely used in aerosol sprays and refrigerants until an

agreement in 1987 to phase them out. But scientists also think that global

warming may be contributing to the phenomenon.

During much of the 1990's there was resistance here to accepting signs that

the risks to people were growing. The warnings of scientists like Bedrich Magas

of Magallanes University, one of the first to emphasize the potential dangers,

were dismissed by local boosters who feared a drop in tourism.

But that changed in September 2000, when the ozone hole opened directly over

Punta Arenas. The Socialist government responded with a far-reaching prevention

and education program that has become visible everywhere.

"It's a new way of living," said Lidia Amarales Osorno, the Chilean

Health Ministry's regional director here. "You'll see the solar stoplight

posted in supermarkets, offices and schools, and we even have an Ozone Brigade

to raise consciousness about this problem."

In elementary schools, a giant penguin named Paul leads a permanent campaign

to teach children the steps they need to take to protect themselves. Many

schools also hoist a flag each morning to alert their pupils' families of the

expected level of ultraviolet rays, and in some poor neighborhoods, skin creams

are even distributed free to youngsters.

"But the truth is that there is only so much that we can do here

ourselves," Dr. Amarales said.

This year, to everyone's bafflement, the situation has been relatively mild.

The ozone hole split in two for only the second time since monitoring began,

with only the smaller part passing over Punta Arenas, winds have been calmer

than usual, and the hole has begun to retract earlier than usual.

But scientists here warn that the problem may persist until the middle of the

century and is likely to worsen through the decade.

|

Punta

Arenas, the planet's most southern city, needs sunblock.

|

The laboratory here has also reported the appearance of smaller ozone holes

in central Chile, and health officials say that the incidence of melanoma, the

most common form of skin cancer, in Santiago, the country's capital, increased

by 105 percent between 1992 and 1998.

Because solar radiation reaches the ground at a more acute angle here than

places farther north, Punta Arenas may actually be at less risk than other parts

of Chile.

But this time of year, atmospheric scientists from all over the world flock

here anyway, drawn by the opportunity to study a rare and little-understood

phenomenon. Their presence, rather than reassuring residents, only adds to their

sense of unease.

"We feel like we are rabbits in a laboratory experiment," said Ivan

Mansilla Vera, 36, an engineer and father of two young children. "Nobody

knows what is going to happen to us."

overnment

scientists have measured a significant drop in atmospheric levels of methyl

bromide, a versatile pesticide that is being phased out of use because it

damages the planet's protective ozone layer.

overnment

scientists have measured a significant drop in atmospheric levels of methyl

bromide, a versatile pesticide that is being phased out of use because it

damages the planet's protective ozone layer.

The scientists say the drop, 13 percent since 1998, is attributable to

mandatory curbs on the chemical under the Montreal Protocol, a 1987 treaty aimed

at restoring the layer, which blocks ultraviolet radiation that could otherwise

raise cancer rates and harm ecosystems.

The researchers, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration,

describe the findings in yesterday's issue of the journal Geophysical Research

Letters.

Methyl bromide, while less common than Freon and other restricted

ozone-damaging substances, breaks down in the air and releases bromine, which

disperses into the stratosphere and vigorously attacks ozone molecules.

But for decades methyl bromide has also been a popular, cheap means of

sterilizing soils, grain silos and shipments of perishable goods.

Environmentalists welcomed the new findings but expressed concern about

recent proposals by the United States and other countries to continue and expand

certain uses of methyl bromide past 2005, when, under the Montreal pact, a ban

is to take effect in industrialized countries.

This year the Bush administration is seeking exemptions to the ban on behalf

of dozens of strawberry and tomato farmers, golf-course owners and other users

of methyl bromide who say no inexpensive alternatives exist.

Federal agriculture officials also want to expand its use in fumigating

imported wood packaging and shipping pallets that may contain Asian longhorn

beetles or other pests.

But David D. Doniger, a policy director for the Natural Resources Defense

Council, said the exemptions were unnecessary and would cause a rise in methyl

bromide use after a steady drop. A variety of pesticides are listed by the

federal government as substitutes for methyl bromide, Dr. Doniger said, adding

that fumigation of imported goods could be ended if shippers were required to

heat wood to kill pests or switch to other kinds of packaging.

The new study projects continued steep declines in methyl bromide in the air

as long as use of the chemical continues to drop.

Those projections do not take into account the possibility of substantial use

under exemptions to the Montreal treaty, said Dr. Stephen A. Montzka, the

government chemist who led the study.

"Without continued worldwide adherence to the restrictions outlined in

the protocol," Dr. Montzka said, "these trends could slow and delay

the recovery of stratospheric ozone."